Inspecting concrete subfloors

Audio for slide 1 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 1 (mp3 |6|KB)

The single issue that has the most potential to cause a problem with a new floor covering is the concrete's moisture content. Another factor is the surface pH - or level of alkalinity.

Because these tests are such a crucial part of the inspection process, we'll cover them separately in the next section of this unit.

So for now we'll look at some of the other issues you should be aware of.

Audio for slide 2 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 2 (mp3 |6|KB)

Curing compounds

Curing compounds are used to seal the surface of fresh concrete to slow down the evaporation process.

Click on the link below for more details on the types of curing compounds available.

More on types of curing compounds

They're generally sprayed onto the surface, but can also be rolled or painted on.

The problem for flooring installers is that they stop glues and cement based toppings from bonding properly to the concrete.

Audio for slide 6 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 6 (mp3 |6|KB)

Laitance

Laitance is a powdery or milky layer of cement and sand on the surface of concrete.

It's often caused by over-watering the fresh concrete or over-trowelling the surface.

Sometimes it occurs when the concrete has dried too quickly because it didn't have a curing membrane on top.

The problem with laitance is that it's loose and friable, and can easily 'delaminate' from the solid concrete below, so any glue or topping applied to it won't be properly bonded to the slab.

Audio for slide 8 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 8 (mp3 |6|KB)

Surface Contaminants

Contaminants include oil, grease, wax, and any other substances that might prevent the glue or topping from bonding to solid concrete.

Like laitance, you need to find out how deep the contaminants have penetrated into the pores of the concrete before you decide on the best method for removal.

For example, a light film of grease on the surface might be able to be removed by scrubbing with a commercial detergent or degreaser.

For contaminants that have penetrated deeper, the only solution may be to grind or blast the surface till you get to clean concrete.

Audio for slide 9 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 9 (mp3 |6|KB)

Cracks

Most cracks occur as a result of shrinkage during the drying process.

Small cracks can easily be filled with an epoxy or polyurethane compound.

Larger cracks may need to be injected with epoxy or filled with a patching compound.

We'll cover this in more detail in the unit: Subfloor coatings and toppings.

Audio for slide 11 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 11 (mp3 |6|KB)

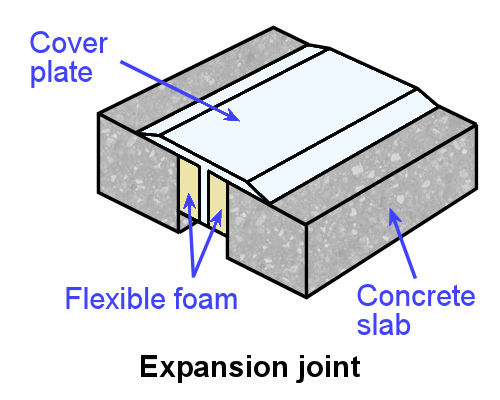

But on large commercial projects there may be joints at regular intervals across the floor.

These joints should never be filled with a patching compound, because it will crack when the concrete moves.

Instead, the joint should be covered by a cover plate in accordance with the specifications for the project.

Audio for slide 12 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 12 (mp3 |6|KB)

Planeness and smoothness

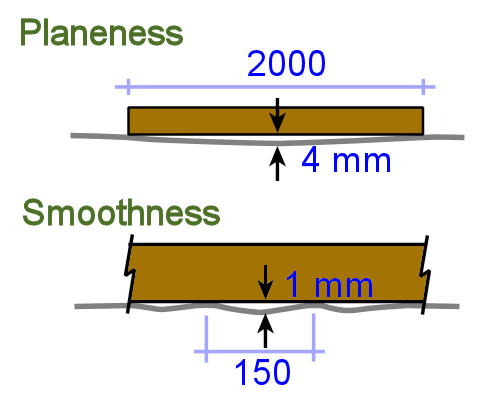

The Australian Standards set limits on the amount of deviation that's allowed from a smooth flat surface.

These tolerances vary depending on the type of floor covering installed.

There are also industry standards and manufacturers' recommendations for particular products.

These might set stricter limitations than the Australian Standards.

Audio for slide 13 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 13 (mp3 |6|KB)

Planeness: When a 2 metre long straightedge is placed on a concrete floor, resting on two points that are 2 metres apart, the maximum deviation from planeness (or 'flatness') is 4 mm.

Smoothness: When a 150 mm long straightedge is placed on a concrete floor, resting on two points, the maximum deviation is 1 mm.

We'll look at the techniques for measuring planeness and smoothness in more detail in the unit: Subfloor coatings and toppings.

Audio for slide 15 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 15 (mp3 |6|KB)

The first symptoms are generally rust stains and a flaking surface.

The condition is sometimes called 'concrete cancer', and if left untreated it can cause major structural damage to the slab.

Audio for slide 16 (mp3 |6|KB)

Audio for slide 16 (mp3 |6|KB)

In some cases it could be because the steel was originally placed too close to the surface or edge of the slab, allowing water to come into contact with it.

In other cases it could result from cracks or damage that have allowed the water to get in.

If the problem is too serious for you to handle with patching compounds, the only solution is to tell the client that a specialist will be needed. This is something they may wish to organise themselves or ask you to handle on their behalf.

Learning activity

Audio 17 (mp3 |6|KB)Even if you're not familiar with expansion joints in concrete, you're sure to have walked over the top of many joints in slab floors - such as in shopping centres, supermarkets and warehouses.

Next time you're in a shopping centre or other large building, have a look for the expansion joints in the floor. Take photos on your mobile phone and share them with your trainer and other learners in your group.

To get an idea of the range of expansion joint designs and cover plates used on concrete floors, do an 'image' search on the internet to see some examples of available products.

Go to

Go to